Page content

Stability

Stability is defined as the strength to stand or endure. As such, it is crucial for young people’s wellbeing and their ability to maintain supportive and caring relationships. We have been tracking the placements of our study population (n=374) since 2000, when they were all under the age of five and in care in Northern Ireland.

Placement stability

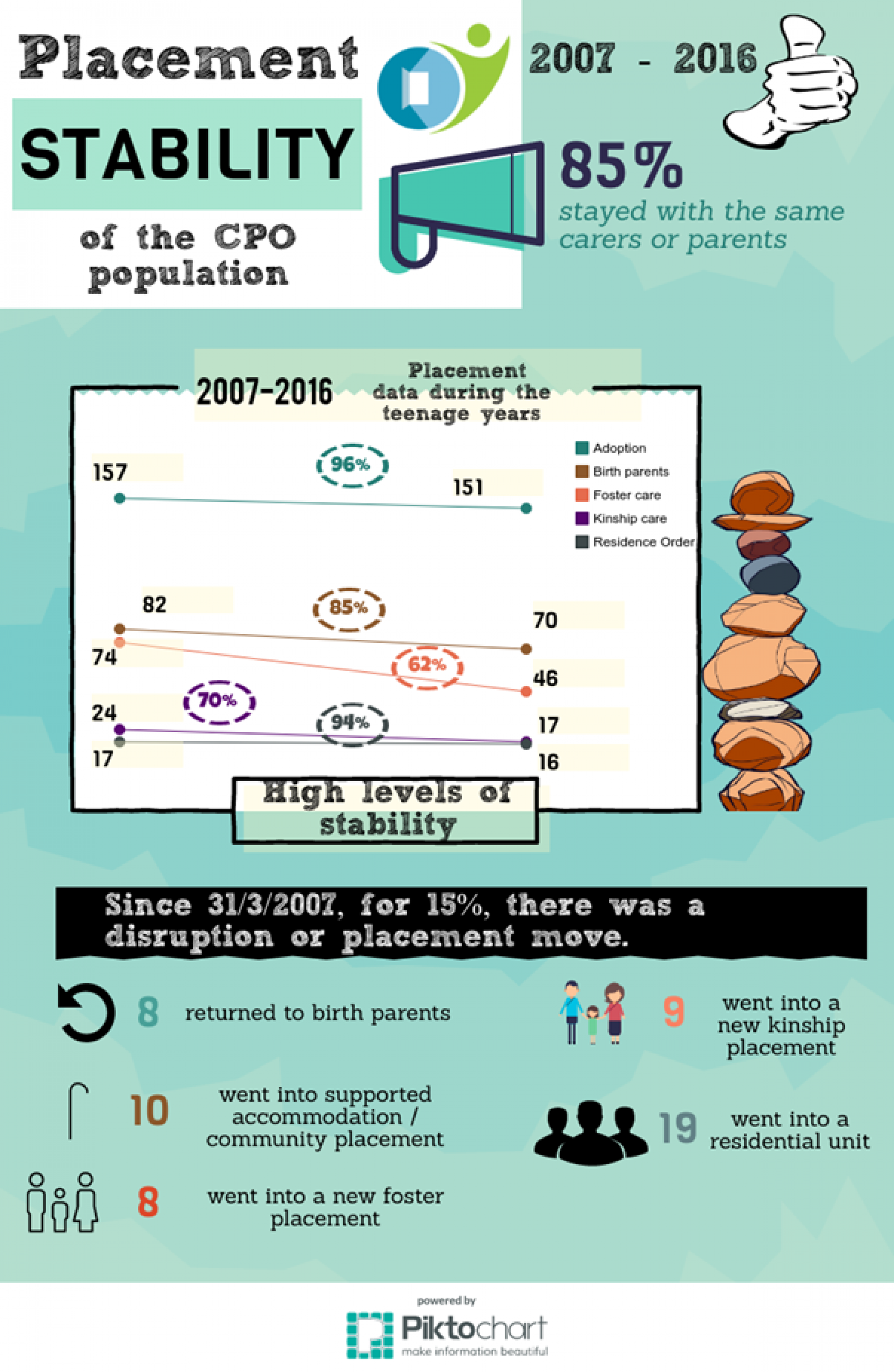

In this blog post, we focus on the stability of the placements that the young people had on 31st March 2007, and whether they were still living there on 31st March 2016 (aged 16 to 21), or at least had remained there until they were 18 years of age. We particularly looked at whether or not young people remained living continuously with the same parents and carers (not just in the same type of placement).

What we found

We found high levels of stability for these young people, as illustrated by the infographic. Clearly, adoption and Residence Order placements provided the highest levels of stability through to 18. The adoption figures may need to be treated with some caution as not all adoptive families are traceable by social services, and it may be the case that some disruptions have occurred that have not been accounted for. However, a rate of 4% would be consistent with Northern Ireland government statistics. The rate of stability for return home placements is also very high. In these circumstances, by stability we mean that the young person did not re-enter the care system.

Rates of stability in foster care and kinship foster care were lower than the other three placement types, but these can be considered as still quite high and are at odds with the notion that foster care is not well placed to provide stability through to 18 for children in the care system. Our findings show that this is clearly not the case. Furthermore, foster placements require statutory leaving care planning by social services with the young person, and these can at times create an inexorable momentum towards care exit. Additionally, evidence is emerging from the study that even where foster and kinship foster care placements have disrupted during the teenage years for young people, the relationships with the carers are often maintained, i.e. the ‘family’ remains intact. The point is that physical endings, i.e. where you live, do not always result in relational endings, i.e. who you consider to be your mum, dad, son, daughter, brother, sister, etc. This notion of relationship permanence in the context of placement instability will be further discussed in a future blog post.