Page content

Stress and parenting

All of us who are parents are familiar with the stresses that can be involved in raising children. Imagine then how difficult this would be if these ‘normal’ stresses were exacerbated by the impact of early childhood trauma. That’s the daily parenting scenario that faces many foster and adoptive parents in Northern Ireland, across the UK, and in many other countries across the world. If parent/carer stress is experienced within the confines of boundaries, without it leading to negative consequences, then it can be a source of stimulation and an opportunity for growth. In contrast, stressed-out parents who are irritable, uncommunicative, critical and harsh in their parenting style are more likely to cause problematic behaviour in their children, which in turn results in further parental stress, thus creating a vicious circle.

Parenting stress across the pathway types

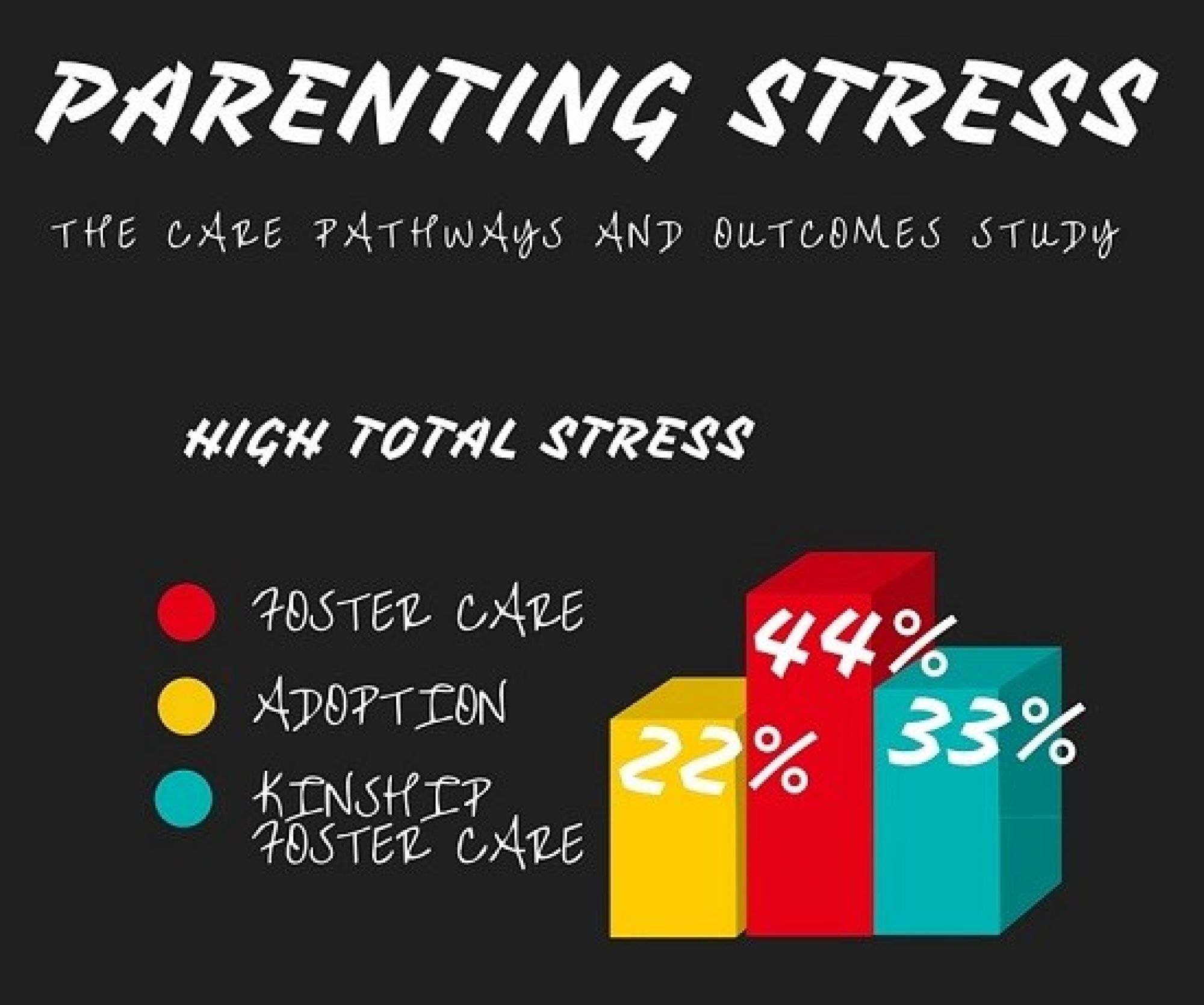

The Care Pathways and Outcomes study is focused on understanding if the experiences of children and parents/carers are different across the various placement types. Parental/carer stress is seen as central to unravelling some of these differences. As such, the issue of parenting/carer stress was examined in the previous phase of the study, applying Abidin’s (1995) Parenting Stress Index (PSI/SF). We found a much higher percentage of foster carers scoring within the abnormal range on the ‘total stress’ component of PSI, compared with adoptive parents. These findings are both surprising and counter-intuitive. This is because foster carers are part of a formal care system, with social workers supporting them and the children they are caring for. This is not the case for adoptive parents and their children, who have no formal access to social service support, yet they appear significantly less stressed. How can this be?

What the research suggests

Several studies have explored stress experienced by foster carers and have found evidence of strain, anxiety and depression related to the stressors of the caregiving role. Research evidence consistently demonstrates that children in care have higher emotional disturbance than the general population. Yet, there is an expectation that when children come into care, their new care placement will ‘provide compensatory experiences of care that enable their positive development’. Given the previous experiences of these children, carers are tasked with providing a substitute nurturing and safe family home for children who typically have medical and health problems, dysfunctional attachments, academic and cognitive problems, and behavioural and psychiatric disorders. However, the same can also be said for adoptive parents, so why the differences in stress levels?

There is some indication that the lives of foster carers appear more complicated than those of adoptive parents in terms of the logistical pressures of caring. They are expected to manage a greater degree of relationships with birth family members than adoptive parents, their own family tensions, the risk of placement disruption, the potential for complaints or allegations, and social work involvement. All of these factors can make fostering a very difficult task. Furthermore, children tend to be placed earlier in adoption than foster care, so there is a decreased probability that the adopted child will have experienced significant trauma as a result of maltreatment and witnessing the breakup of the family home.

Future work

There have been clear indications from this study that the experience of parent and carer stress may be different between foster carers and adoptive parents, and this can impact on placement stability. It will continue to be important to examine if these differences remain, as the young people progress through the late teenage years and into early adulthood. We will aim to further explore the reasons for these apparent differences, and to examine the impact this may have on placement stability and other outcome measures.