By Pete Hodson, Research Associate, Museums, Crisis & Covid-19

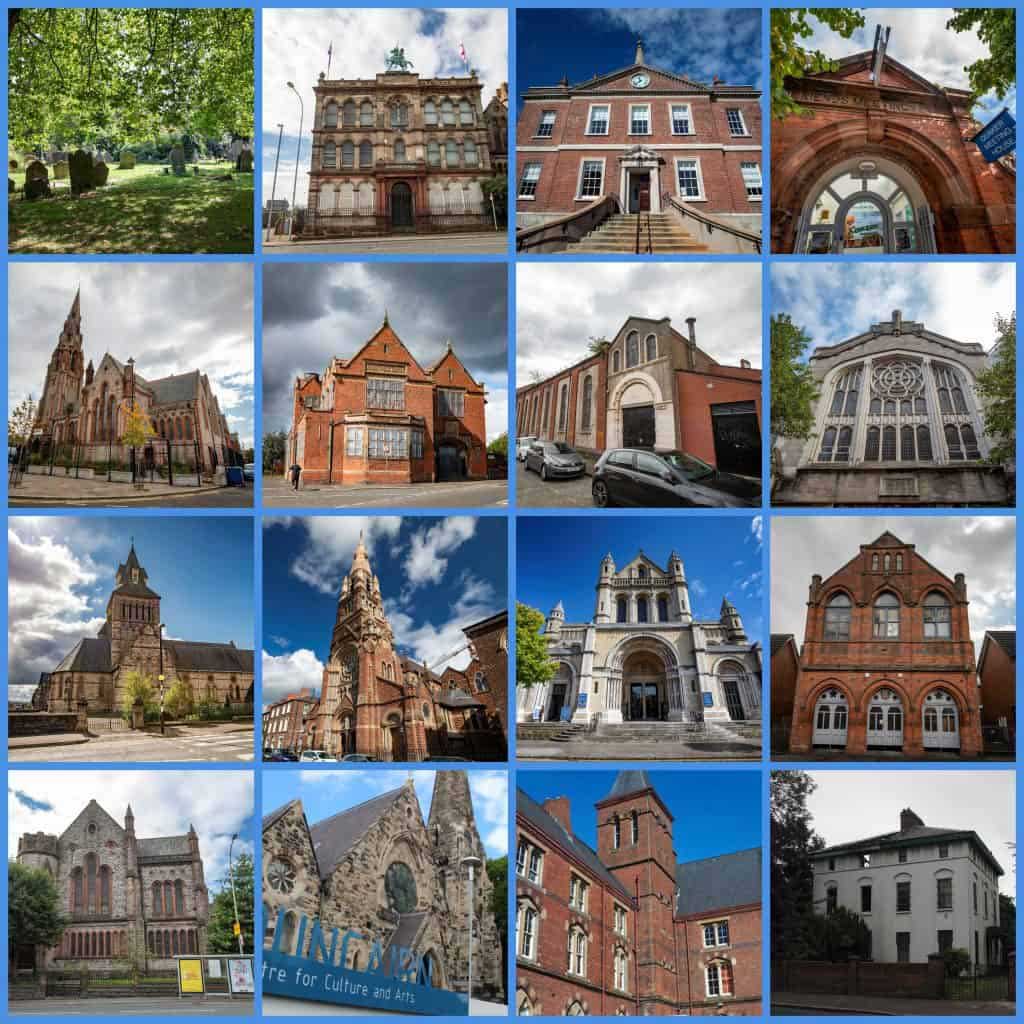

In January 2020 I was recruited as an archive researcher for Great Place North Belfast (GPNB). This three-year heritage project, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Belfast Charitable Society, brings together fourteen organisations responsible for a range of historical assets in North Belfast. Members include Clifton House, the North Belfast Working Men’s Club and the Indian Community Centre.

Since 2017, Great Place has funded a number of projects across the UK. The scheme funds heritage-led regeneration in areas experiencing deprivation, ill-health and limited educational and cultural access. Great Place seeks to inspire pride in place through enhanced civic understanding of local built and intangible heritage.

The North Belfast Heritage Cluster formed in 2018 and successfully applied for Great Place funding to fulfil these objectives. In North Belfast, an area deeply scarred by the Troubles, the project also seeks to build awareness of shared history.

My initial role at GPNB involved building up a catalogue of key archival documents relating to individual cluster members. These were found at a number of local repositories including PRONI, the Linenhall Library and Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections. I also produced a report outlining the value of oral history interviews to build up a picture of North Belfast’s social history which – in common with other parts of the city – is underdeveloped.

Members of the North Belfast Heritage Cluster.

Eight weeks into the job, Covid-19 intervened. The first national lockdown coincided with my own brush with the virus and a period off sick. My return to work (now the kitchen table) in April saw a complete re-write of my job role. Like many others working in the heritage and museum sector, the impact of national lockdown was sharp, disorientating and the catalyst for creative thinking. If we couldn’t reach our cluster members, or the public, through traditional means, what other options were available?

Heritage audience engagement during lockdown

Like most – if not all – heritage projects, we turned to digital media as a means of advancing our research and impact. The GPNB Twitter and Facebook pages had, until this point, been used for sporadic news updates. Within four weeks they became our sole delivery medium and the focus of a structured social media campaign. Working with cluster members, we co-developed a digital project called ‘Telling Our Stories’. The history of each cluster member would be told using a physical artifact, audio interview with a key figure, and a research blog post.

With all libraries and archives shut, accessing historical documents remained a problem. The online Irish Newspaper Archives and other digitised sources allowed us to research the diverse organisations that comprise the North Belfast Heritage Cluster. ‘Telling Our Stories’ proved successful and garnered positive feedback from both cluster members and the public. GPNB Twitter followers increased by 44.7% between June and September 2020.

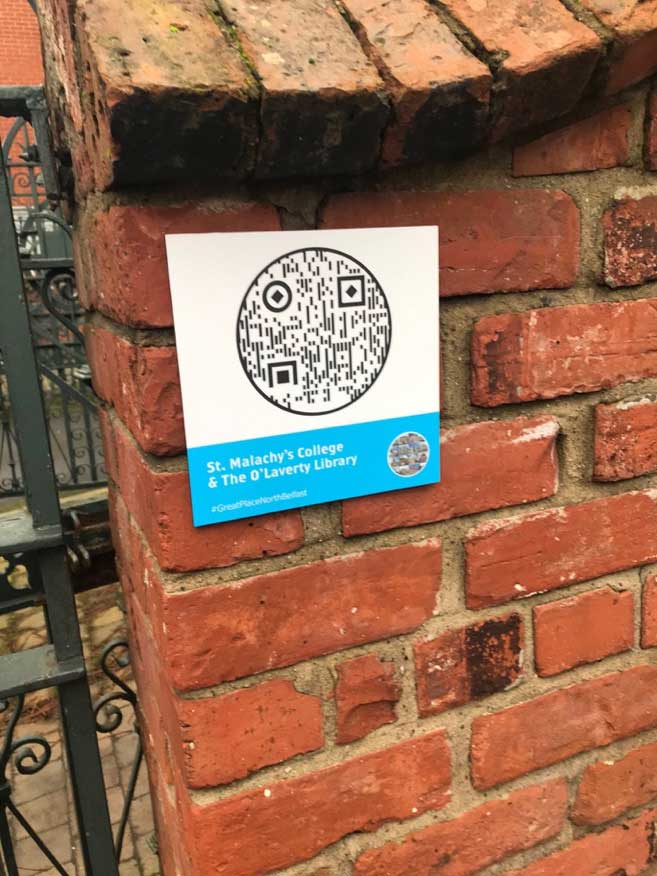

To make further use of this material, the North Belfast Heritage Trail was launched in December 2020. Signs affixed to the outside of each cluster member enable passers-by to scan barcodes (using smartphones) and read and listen to historical content. With the buildings remaining shut for the foreseeable future, the heritage trail facilitates a virtual peek inside historic buildings and a Covid-secure means of engaging with the public.

North Belfast Walking Trail barcode outside St Malachy's College.

Social media, though a useful tool in our armoury throughout the pandemic, has its limitations. Some groups do not have access to (or familiarity with) digital platforms. Ramped-up social media output did, however, connect us with new international audiences as our analytics report later revealed.

Our (unavoidable) focus on developing digital content caused the postponement of other key project areas. This included hands-on conservation and cataloguing work on behalf of each organisation, and a planned two-day programme of cultural events including North Belfast’s first heritage festival.

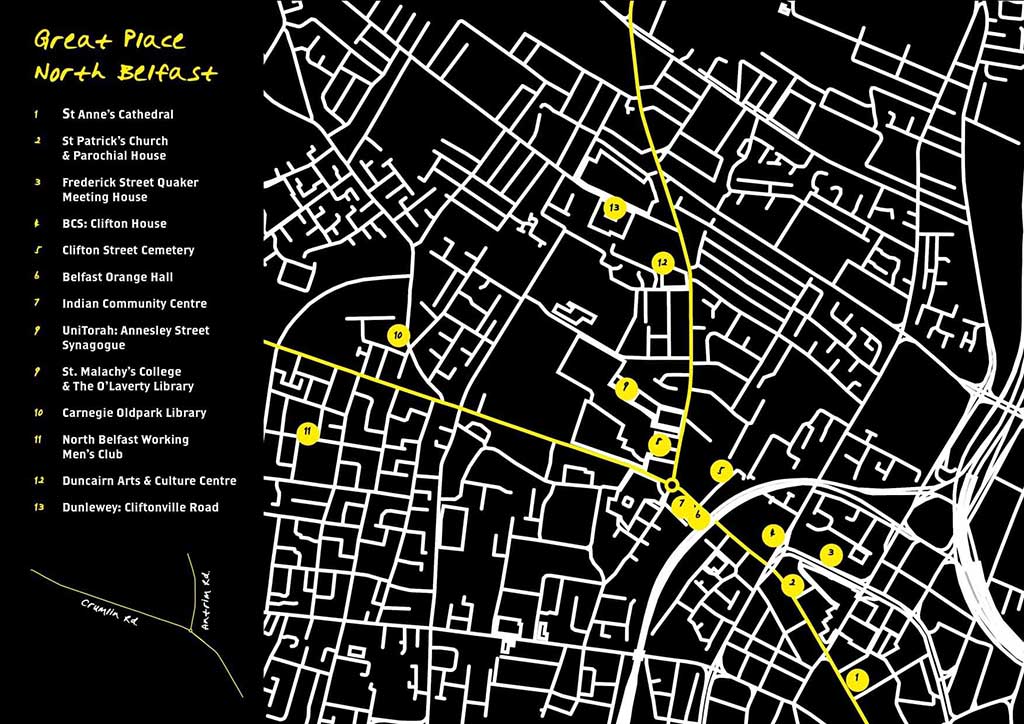

IMAGE 3: North Belfast Heritage Trail map.

What we learned from Covid-19

Covid-19 has sharpened our awareness of social inequality and rendered visible the extent of economic precarity. Early on in the pandemic, for example, the Belfast Charitable Society donated laptops for school children without access to online facilities. Covid-19 has demonstrated the need to go beyond surface-deep urban regeneration, the sort that just adds new lighting and street furniture, and tackle underlying issues.

Our research work for GPNB uncovered, among many things, the contribution of women and ethnic minorities to the cultural and social fabric of North Belfast. Building awareness of this heritage has the potential to change the area’s narrative, build community resilience and encourage wider appreciation of North Belfast’s shared history. Importantly, GPNB continued to act as a forum throughout the pandemic (via regular Zoom meetings) ensuring that redevelopment plans for North Belfast reflect community needs and aspirations.

Discover more about Great Place North Belfast via their website

Dr Pete Hodson worked for GPNB until January 2021. He now works as Research Associate on the UKRI-funded project ‘Museums, Crisis and Covid-19: Vitality and Vulnerabilities’. This multi-disciplinary project team, led by Professor Elizabeth Crooke, is investigating how the museum sector will emerge and refocus in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.