The historic museum building

The concept of a museum has since the nineteenth-century presupposed the existence of a building where objects are assembled together and made meaningful in relation to each other to form a collection. While the origin of the museum as a physical space may have been in the humble ‘cabinet of curiousities’ (Senior, 2005: online], as museums came to serve as national, institutional, commercial or personal projections of power, wealth and/or erudition, the buildings became ever grander: the discourses of natural science superseding those of supernatural faith, with the museum becoming a ‘cathedral to nature’ or a ‘temple of science’. The spatial organization of the collections housed within such buildings articulated the taxonomic systems which the museums used to make sense of the world. So, it was that the visitor journey within the museum created the embodied experience of specific museological discourses through the spatial organization of the building and objects within it (Ntoulia, 2017: online).

The museum building today

Even today the concept of a museum as a building is still pervasive since it is easy to miss the slippage between institutions, buildings and collections of material things. Hilary Porter identified the formula ‘traditional museum = building + collection + expert staff + public visitors’ (2017: online]). Even where there is a deliberate attempt to re-define the museum as in the ICOM Define: Standing Committee for the Museum Definition there is still an implicit commitment to a building in the idea of a ‘permanent, not-for-profit institution [that] researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible cultural and natural heritage’.

Beyond a building: the distributed museum

The extension of the museum beyond the walls of institutional buildings has of course been an important aspect of outreach activities in many museums. Object loan boxes such as those available from the Northern Ireland War Memorial are just one of the ways in which the educational function of museums have extended beyond the physical museum space. The museum also offers outreach workshops that can be placed in other spaces and buildings, such as schools.

A more significant extension beyond the museum building was proposed by Nancy Proctor in her proposal for the ‘distributed network model’ for the 21st Century museum. Using the power of technology, this new museum would place less emphasis on authentic original objects and more on sequences of experiences ‘assembled collaboratively along the many-branched paths of a rhizome. In the museum as distributed network, content and experience creation resembles atoms coming together and reforming on new platforms to create new molecules, or ‘choose your own ending’ adventure stories’ (2010: online).

The phygital turn

Within many states, the public health response to the Covid-19 pandemic was to lockdown populations and close indoor spaces, including museums. As Sandro Debono notes this resulted in ‘an unexpected and increased shift within museums towards digital and online strategies. For many months, digital was the tool, albeit not the only one, with which museums could stay relevant to their publics and audiences.’ (2021: 156). One strand of this current project has been to explore and support this turn to the digital within the Northern Ireland museum sector. See the briefing report Museums, Covid and Digital Media.

Debono proposes the necessity of turning to the ‘phygital’ where digital and physical experiences might ‘coexist, cross-reference or correlate with each other much more than previously believed’. The National Museums Northern Ireland project Museum on the Move, for example, is a programme where museum staff deliver live and interactive workshops for primary schools via video technology to pupils in the classroom who can ask questions and explore real objects on loan from the museum.

Next steps: emporiums of history?

An even more profound response might be generated by picking up on a proposal within the ecomuseum movement (Davis 1999). Corsane suggested that one of the indicators of an ecomuseum is that it ‘Takes the form of a ‘fragmented museum,’ consisting of a network with a hub and antennae of different buildings and sites’. The extension of this idea of distributing the museum might overcome the restrictions on people gathering within indoor spaces faced during lockdown and offer affordances previously unexplored for visitor engagement.

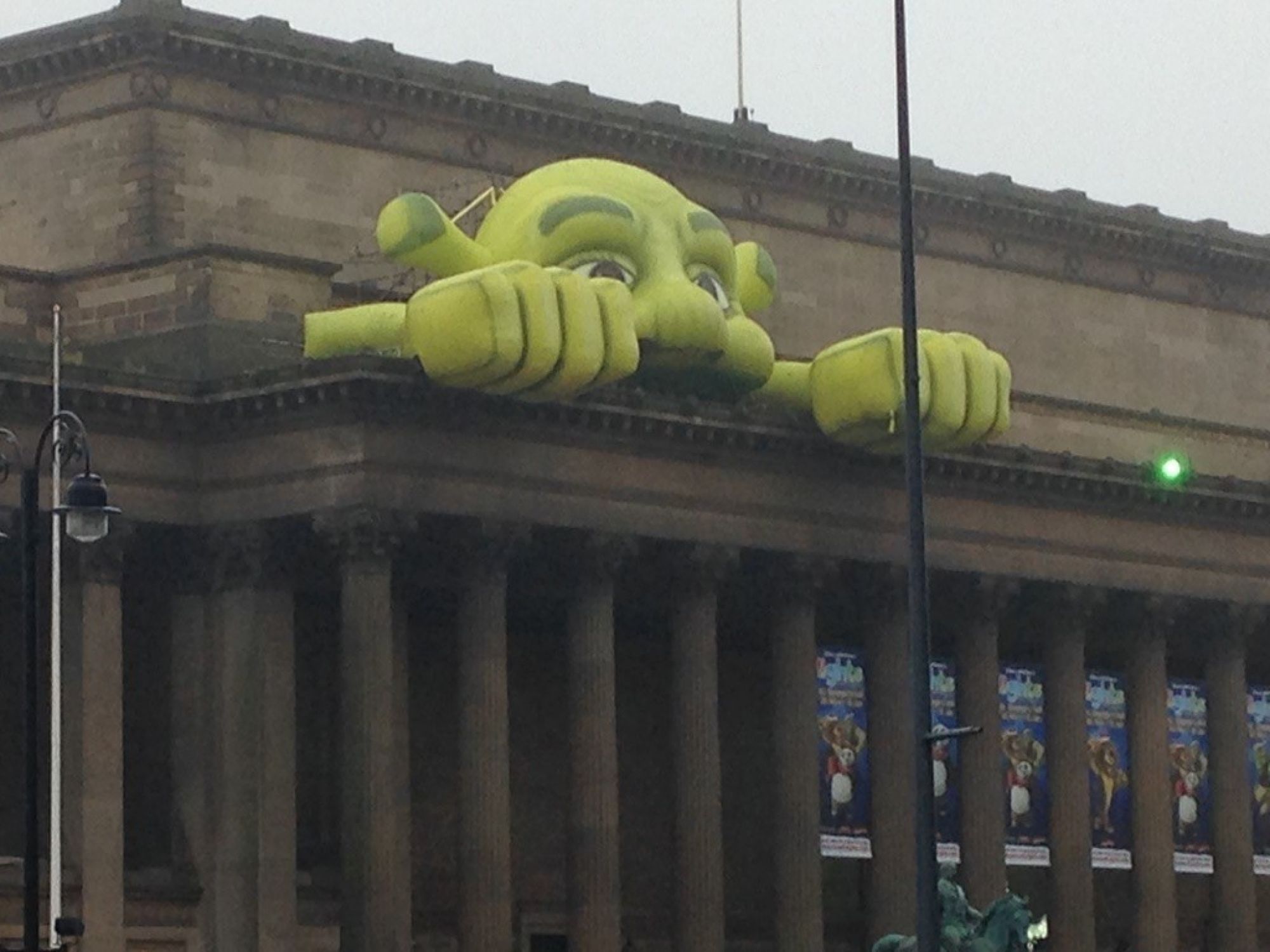

The emptying out of retail spaces from urban centres for example might provide shop windows as exhibition spaces. In 2015 the Window Museum initiative launched in Harlem, New York City to use the windows of empty commercial spaces to access ‘an archive of multimedia art, performance, mailart and games.’ It was an idea picked up elsewhere during the pandemic. In 2020, Platform Arts moved their artist-led gallery and studio spaces to the Connswater shopping centre in East Belfast. In Ryde on the Isle of Wight ‘Spring Window’ installations were created in April 2021 within a designated ‘Heritage Action Zone’ to celebrate the High Street’s rich cultural Heritage. In August 2021, York’s JORVIK Viking Centre developed what Adrian Murphy termed ‘an inclusive portfolio of 24-hour exhibitions created specifically for empty retail units that will be made available to hire by other towns and cities that want to inject a bit of life into their high streets.’ (2021: online)

For many curators, this proposal for distributing the proposal may be as welcome as a 1949 lecture by Elias Svedberg on museum design was to Sir Leigh Ashton, the then Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Ashton declared, ‘I am a museum man myself, but I think the technique of the shop window is not particularly suitable to museums. I think you should go inside museums because you want to’ (1949: 864). For a sector recovering from lockdown and facing the renewed challenges of attracting visitors to buildings that may be becoming increasingly expensive to open, it may be worth exploring the shop window as an exhibition space, with the museum less a sacred site, than a network of emporiums of history.

Further reading

Davis, Peter (1999). Ecomuseums: A Sense of Place, London: Leicester University Press.

Corsane, Gerard (2006) ‘Using ecomuseum indicators to evaluate the Robben Island Museum and World Heritage Site,’ Landscape Research, 31:4, 399-418, DOI: 10.1080/01426390601004400

Debono , Sandro (2021) ‘Thinking Phygital: A Museological Framework of Predictive Futures.’ Museum International, 73:3-4, 156-167, DOI: 10.1080/13500775.2021.2016287

Ntoulia, Elissavet (2017). ‘The birth of the public museum.’ Wellcome Collection [online]. Available: https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/W_0kHhEAADUAbHiJ. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Proctor, Nancy (2010) ‘The Museum as Distributed Network, a 21st Century Model.’ Museum-iD [online]. Available: http://museum-id.com/museum-distributed-network-21st-century-model-nancy-proctor/. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Senior, John (2005) ‘The Rise of Museums.’ The Open University, Open Learn [online]. Available: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/the-rise-museums. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Svedberg, Elias (1949) Museum Display’. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 97: 4804, 850-865. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41363943.